Tom Stoddart, Every Picture Tells a Story - Tuesday 5th March 2019.

On Tuesday 5th March, Morpeth Camera Club were very pleased to welcome the internationally acclaimed photojournalist Tom

Stoddart Hon FRPS with a talk entitled ‘Every Picture Tells a Story’. He opened the evening by saying that he had been born in

Morpeth, brought up in Beadnell and began his career at the Berwick Advertiser. He was told at the time that as a photographer

he would enjoy a champagne lifestyle on a beer salary, and over the past fifty years, he said, he has enjoyed an incredible life

travelling to many countries.

Photojournalism is how he makes his living, it takes blood, sweat and tears to capture important and dangerous events, and this

is the reason that these images cannot be just given away. He has worked for organisations such as Shelterbox, an international

disaster relief charity; his photographs taken at the Rohingya refugee camp illustrated the harsh living conditions during the mass migration of people from Myanmar. Charities did not always want tragic images of starvation, they wanted to show inspirational

pictures to encourage donations, but as Tom said, an image of a smiling child doesn’t tell the whole story and people need to

see the other side.

Tom continued with a story of a photo shoot of Queen Rania of Jordan explaining the lengthy organisation, preparation and time restraints, but once the images are handed over to the editor any decision making on choice of pictures to use are out of one’s

control. In contrast we were then transported to the North East with photographs taken five years ago at one of the busiest food

banks, where people told him their stories, resulting in images of people whose faces were etched with pain and anguish.

Harrowing images taken at Lesbos, followed with scenes of pandemonium as refugees landed on the beaches. Carrying their possessions, even wheelchairs, capturing the stricken faces of the people, why, Tom said, would they be here is they were not desperate. Why does he work in black and white? It’s simple, he said, if you shoot in colour you see their clothes, if you shoot

in black and white, you see their souls. When witnessing personal tragedy, you must be confident that you have the right to be

there he said and there is no point in going unless you get in close.

It is not only about capturing what you see but what you feel. Images of the pushing down of the first section of the Berlin Wall

by the hands of the crowds of determined people followed. Working in association with Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors without Borders, resulted in Tom capturing incredibly powerful images of famine and the starving in Sudan which Tom said would hopefully embarrass the politicians. The aim is not just to shoot horror, it is a means to document everything and cause outrage. We saw a shocking image of food being stolen from a starving boy but what isn’t seen is that after the shot it taken, Tom fetched more food

for the boy, but, he said, if you do get involved quite often you are just taking up valuable space from trained medics.

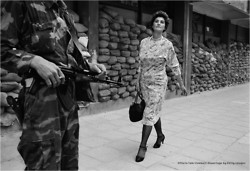

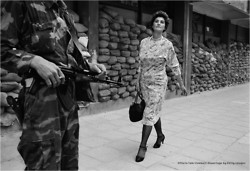

Images followed of ‘sniper alley’ in Sarajevo, where ordinary people take their lives into their own hands by dodging snipers on

their way to work. Proud people who, during 47 months in siege and major conflict, still strived to look their best, together with

grief stricken mothers who had to send their children away from the war zone to safety. Women in conflicts, bravely holding the

families together by finding water and bread, defiantly well dressed, are a source of inspiration to Tom. It is stressful, he said but

it is the simple business of finding and capturing a moment for the world to see, and then leave. Tom said it is both interesting

and scary to look back at his photographs, but he sometimes follows up stories to see how people are and in the case of one

mother and her evacuee child, he tracked them down to where they are happily settled in Australia.

The hard part of his work is being there, watching the sick and dying and it has a toll on one’s private life, it is hard to keep some

kind of ‘look at this’ mentality when mass graves become the norm for children to see and when he sees young boys handling

Kalashnikovs, laughing. As a freelance photographer, Tom prefers to work alone and not in a gang because in his opinion groups

can sometimes make bad decisions.

We saw images of Rwandan genocide and of cholera ridden refugees flooding into Zaire, in the days of film photography Tom often

found himself at airports begging passengers to take his rolls of film back to the UK. During the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo he came across bombed homes where he found abandoned weathered photographs, a poignant reminder of family life in happier times.

At the time of 9/11 Tom’s picture editor told him not to cover it but he felt compelled to go. We saw passengers on the first return

commute on the Statton Island Ferry, looking over to the scene of destruction. He said there was complete silence on the journey

over, and you could sense the silence in this powerful image. Missing person pictures on mail boxes appealing for information and

sellers of T-shirts announcing ‘We Will Prevail’, captured the mood perfectly.

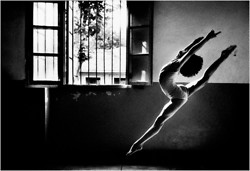

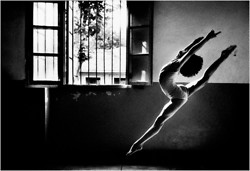

There were photographs of the 539 assault squadron on the eve of the liberation south of Basra, of emotionally tired soldiers who

had to stay focussed even after being informed of the deaths of comrades. He captured scenes during the AIDs epidemic in Zambia

and Zimbabwe; in another country he had to bribe his way into a state gymnasium to record shots of their methods of achieving sporting prowess to bring international glory and prestige to their country. Stark monochrome images of refugee camp life, child

labour factories, iron harvest trenches in the Somme, and women and children digging putrid water wells in Sudan followed.

Amusing stories ‘from the inside’ came next of politicians such as Thatcher, Blair and Cameron, images taken during both leisure

and stressful times. These were intended to be ’a day in the life of’, portrayals but he was often only given 30 seconds in which to

take the photographs.

Ending his presentation he said that the young think that the profession is cool but it is a challenging job and it’s a privilege, he

has lost a lot of friends along the way and at the end of the day it is not worth risking your life for, and with no insurance you are

out there on your own. He ended by saying that ‘for most of his career he got by through just sheer bloody mindedness!’

This evening 'Every picture did tell a Story', thought provoking images together with effortless commentary, it is easy to see why

Tom’s photographs have international acclaim.

Stoddart Hon FRPS with a talk entitled ‘Every Picture Tells a Story’. He opened the evening by saying that he had been born in

Morpeth, brought up in Beadnell and began his career at the Berwick Advertiser. He was told at the time that as a photographer

he would enjoy a champagne lifestyle on a beer salary, and over the past fifty years, he said, he has enjoyed an incredible life

travelling to many countries.

Photojournalism is how he makes his living, it takes blood, sweat and tears to capture important and dangerous events, and this

is the reason that these images cannot be just given away. He has worked for organisations such as Shelterbox, an international

disaster relief charity; his photographs taken at the Rohingya refugee camp illustrated the harsh living conditions during the mass migration of people from Myanmar. Charities did not always want tragic images of starvation, they wanted to show inspirational

pictures to encourage donations, but as Tom said, an image of a smiling child doesn’t tell the whole story and people need to

see the other side.

Tom continued with a story of a photo shoot of Queen Rania of Jordan explaining the lengthy organisation, preparation and time restraints, but once the images are handed over to the editor any decision making on choice of pictures to use are out of one’s

control. In contrast we were then transported to the North East with photographs taken five years ago at one of the busiest food

banks, where people told him their stories, resulting in images of people whose faces were etched with pain and anguish.

Harrowing images taken at Lesbos, followed with scenes of pandemonium as refugees landed on the beaches. Carrying their possessions, even wheelchairs, capturing the stricken faces of the people, why, Tom said, would they be here is they were not desperate. Why does he work in black and white? It’s simple, he said, if you shoot in colour you see their clothes, if you shoot

in black and white, you see their souls. When witnessing personal tragedy, you must be confident that you have the right to be

there he said and there is no point in going unless you get in close.

It is not only about capturing what you see but what you feel. Images of the pushing down of the first section of the Berlin Wall

by the hands of the crowds of determined people followed. Working in association with Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors without Borders, resulted in Tom capturing incredibly powerful images of famine and the starving in Sudan which Tom said would hopefully embarrass the politicians. The aim is not just to shoot horror, it is a means to document everything and cause outrage. We saw a shocking image of food being stolen from a starving boy but what isn’t seen is that after the shot it taken, Tom fetched more food

for the boy, but, he said, if you do get involved quite often you are just taking up valuable space from trained medics.

Images followed of ‘sniper alley’ in Sarajevo, where ordinary people take their lives into their own hands by dodging snipers on

their way to work. Proud people who, during 47 months in siege and major conflict, still strived to look their best, together with

grief stricken mothers who had to send their children away from the war zone to safety. Women in conflicts, bravely holding the

families together by finding water and bread, defiantly well dressed, are a source of inspiration to Tom. It is stressful, he said but

it is the simple business of finding and capturing a moment for the world to see, and then leave. Tom said it is both interesting

and scary to look back at his photographs, but he sometimes follows up stories to see how people are and in the case of one

mother and her evacuee child, he tracked them down to where they are happily settled in Australia.

The hard part of his work is being there, watching the sick and dying and it has a toll on one’s private life, it is hard to keep some

kind of ‘look at this’ mentality when mass graves become the norm for children to see and when he sees young boys handling

Kalashnikovs, laughing. As a freelance photographer, Tom prefers to work alone and not in a gang because in his opinion groups

can sometimes make bad decisions.

We saw images of Rwandan genocide and of cholera ridden refugees flooding into Zaire, in the days of film photography Tom often

found himself at airports begging passengers to take his rolls of film back to the UK. During the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo he came across bombed homes where he found abandoned weathered photographs, a poignant reminder of family life in happier times.

At the time of 9/11 Tom’s picture editor told him not to cover it but he felt compelled to go. We saw passengers on the first return

commute on the Statton Island Ferry, looking over to the scene of destruction. He said there was complete silence on the journey

over, and you could sense the silence in this powerful image. Missing person pictures on mail boxes appealing for information and

sellers of T-shirts announcing ‘We Will Prevail’, captured the mood perfectly.

There were photographs of the 539 assault squadron on the eve of the liberation south of Basra, of emotionally tired soldiers who

had to stay focussed even after being informed of the deaths of comrades. He captured scenes during the AIDs epidemic in Zambia

and Zimbabwe; in another country he had to bribe his way into a state gymnasium to record shots of their methods of achieving sporting prowess to bring international glory and prestige to their country. Stark monochrome images of refugee camp life, child

labour factories, iron harvest trenches in the Somme, and women and children digging putrid water wells in Sudan followed.

Amusing stories ‘from the inside’ came next of politicians such as Thatcher, Blair and Cameron, images taken during both leisure

and stressful times. These were intended to be ’a day in the life of’, portrayals but he was often only given 30 seconds in which to

take the photographs.

Ending his presentation he said that the young think that the profession is cool but it is a challenging job and it’s a privilege, he

has lost a lot of friends along the way and at the end of the day it is not worth risking your life for, and with no insurance you are

out there on your own. He ended by saying that ‘for most of his career he got by through just sheer bloody mindedness!’

This evening 'Every picture did tell a Story', thought provoking images together with effortless commentary, it is easy to see why

Tom’s photographs have international acclaim.